© Conservation International/photo by Daniela Calvo

The theory behind Grow?

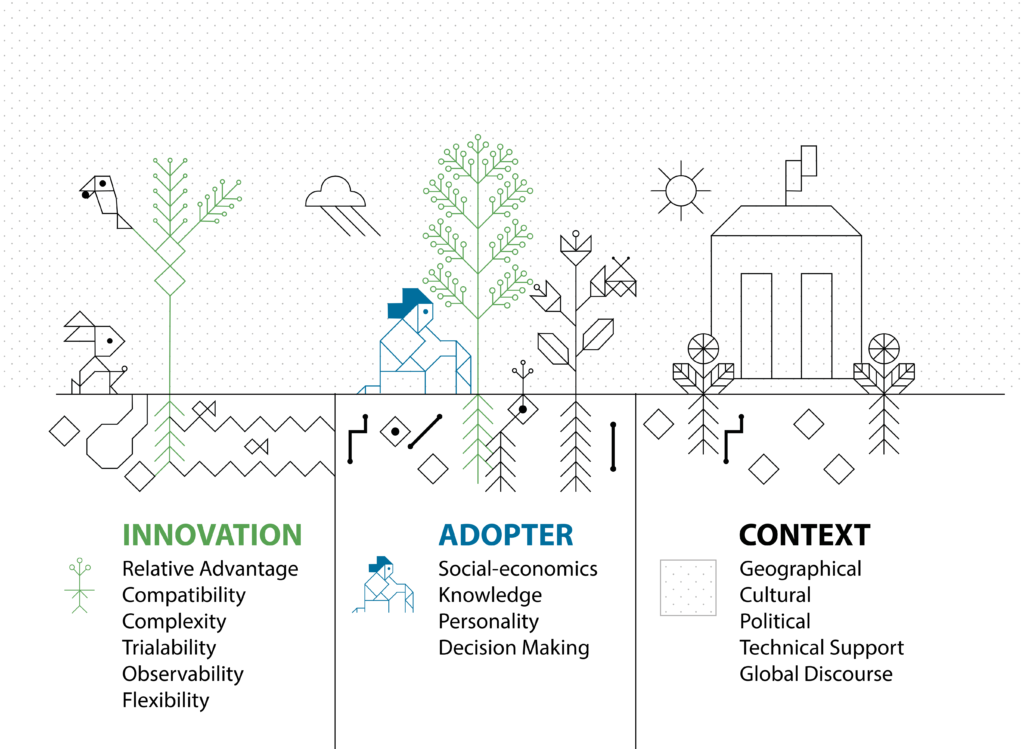

Grow draws on Diffusion of Innovations theory to inform conservation practice. The diversity of initiatives, adopters, and context increases the complexity of applying common frameworks. This theory has been tested across diverse fields and for various applications such as health policies, communication, agricultural technologies, global policies, and increasingly conservation. We believe this conceptual framing is broad enough to encapsulate many conservation initiatives.

Diffusion of Innovations theory propounds a radically different approach to most other theories of change. Instead of persuading individuals to change, the theory sees change as primarily about the evolution or “reinvention” of innovations so they better fit the needs of adopter individuals and groups.

We have integrated existing theoretical frameworks on Diffusion of Innovations to develop a framework for the diffusion of conservation initiatives. We highlight three components important for scaling: initiatives, adopters, and context. Additionally, within each component, we identify attributes and factors that shape diffusion.

Diffusion of Innovation theory focuses on three questions regarding the process of social change:

- What attributes of an innovation make it spread successfully?

- Who is more likely to adopt an innovation?

- Under what contexts do innovations spread more easily?

Glossary

Grow should be considered alongside Catalyzing conservation at scale: A practitioner’s handbook. This handbook details the conceptual framework, factors influencing adoption, and caveats.

General Concepts:

The act of the “adopter” deciding to partake in a new initiative, whether by signing a contract, implementing an action, buying a product, or changing behavior.

The process by which “prior adoption of a trait or practice in a population alters the probability of adoption for remaining non adopters.”

Policies, programs, or projects designed for climate mitigation, conservation, restoration, or sustainable livelihoods.

Policies, programs, or projects (initiatives) perceived as new by the adopter.

Expanding, adapting, and sustaining initiatives in different places and over time.

Innovation Attributes:

The degree to which an initiative is perceived as being better than the idea, practice, or object that precedes it.

The degree to which the initiative is perceived as consistent with existing values, existing actions, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters.

The degree to which the initiative is perceived as relatively difficult to understand and use.

The degree to which the initiative may be experimented with on a limited basis.

The degree to which the initiative and the results of that practice are visible (observable or communicated) to others.

The ability to transform the initiative to something that aligns with the adopter’s desires and constraints.

Adopter Attributes:

The social and economic characteristics of an individual that influence the ability to implement or learn about the initiative. These include education, skills, relative wealth, organizational size, and financial resources.

The degree to which an adopter’s risk orientation, favorable attitude towards change, and spirit of competition influence adoption.

The degree to which the adopter is familiar with the initiative and its consequences through existing knowledge and skill set or acquisition of new skills and knowledge.

Decision-making arrangements specify the rights of individuals or groups to make choices regarding various aspects of conservation initiative design and management.

Context Attributes:

Settings that affect adoption by influencing the applicability of the initiative to the ecological infrastructures of the potential adopter and by exerting spatial effects of geographical proximity.

The degree to which factors such as belief systems, traditionalism, homogeneity, and socialization of actors, influence the adoption of the initiative.

The degree to which government policies, political structure, and political character change the relative advantage of the initiative or the ability to implement it.

We define extension broadly to include public and private sector activities relating to technology transfer, education, human resource development, and sharing of information which influences the adoption and implementation of the initiative.

The degree to which actors around the world are influenced by: (1) Institutionalization (the spread of ideas and behaviors that are supported by different organizations); (2) Global technology (the spread of innovation facilitated by multinational corporations), and (3) World connectedness (access to information via communication systems or media).

References

1 Alvergne, A., Gibson, M. A., Gurmu, E. & Mace, R. Social transmission and the spread of modern contraception in rural Ethiopia. PLoS One6, e22515 (2011). https://doi.org:10.1371/journal.pone.0022515

2 Aral, S. & Walker, D. Identifying influential and susceptible members of social networks. Science337, 337-341 (2012). https://doi.org:10.1126/science.1215842

3 Barstow, C. K. et al. Designing and piloting a program to provide water filters and improved cookstoves in Rwanda. PLoS One9, e92403 (2014). https://doi.org:10.1371/journal.pone.0092403

4 Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P. & Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly82, 581-629 (2004). https://doi.org:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

5 Haenssgen, M. J. & Ariana, P. The social implications of technology diffusion: Uncovering the unintended consequences of people’s health-related mobile phone use in rural India and China. World Development94, 286-304 (2017). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.014

6 Masuda, Y. J. et al. Innovation diffusion within large environmental NGOs through informal network agents. Nature Sustainability1, 190-197 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41893-018-0045-9

7 Gilles, J. L., Thomas, J. L., Valdivia, C. & Yucra, E. S. Laggards or leaders: Conservers of traditional agricultural knowledge in Bolivia. Rural Sociology78, 51-74 (2013). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12001

8 Pannell, D. J. et al. Understanding and promoting adoption of conservation practices by rural landholders. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture46, 1407-1424 (2006).

9 Kelebe, H. E., Ayimut, K. M., Berhe, G. H. & Hintsa, K. Determinants for adoption decision of small scale biogas technology by rural households in Tigray, Ethiopia. Energy Economics66, 272-278 (2017). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2017.06.022

10 Wejnert, B. Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: A conceptual framework. Annual Review of Sociology28, 297-326 (2002). https://doi.org:10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141051

11 Walker, J. L. The Diffusion of Innovations among the American States. The American Political Science Review63, 880-899 (1969). https://doi.org:10.2307/1954434

12 Wang, C.-T. L. & Hosoki, R. I. From global to local: Transnational linkages, global influences, and Taiwan’s environmental NGOs. Sociological Perspectives59, 561-581 (2016).

13 Solingen, E. Of dominoes and firewalls: The domestic, regional, and global politics of international diffusion. International Studies Quarterly56, 631-644 (2012).

14 Romero-de-Diego, C. et al. Drivers of adoption and spread of wildlife management initiatives in Mexico. Conservation Science and Practice3, e438 (2021). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.438

15 Mills, M. et al. How conservation initiatives go to scale. Nature Sustainability2, 935-940 (2019). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41893-019-0384-1

16 Emily, L. B. et al. The importance of future generations and conflict management in conservation. Conservation Science and Practice3 (2021). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.488

17 Mahajan, S. L. et al. A theory-based framework for understanding the establishment, persistence, and diffusion of community-based conservation. Conservation Science and Practice3, e299 (2021). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.299

18 Mascia, M. B. & Mills, M. When conservation goes viral: The diffusion of innovative biodiversity conservation policies and practices. Conservation Letters11, e12442 (2018). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12442

19 Salafsky, N. & Margoluis, R. Pathways to Success: Taking Conservation to Scale in Complex Systems. 1-328 (2022).

20 Salafsky, N., Suresh, V. & Margoluis, R. Taking nature-based solutions programs to scale. (2021).

21 Battista, W., Tourgee, A., Wu, C. & Fujita, R. How to achieve conservation outcomes at scale: An evaluation of scaling principles. Frontiers in Marine Science3 (2017). https://doi.org:10.3389/fmars.2016.00278

22 Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of Innovations. 5th edn, 1-576 (Simon and Schuster, 2003).

23 Kuehne, G. et al. Predicting farmer uptake of new agricultural practices: A tool for research, extension and policy. Agricultural Systems156, 115-125 (2017). https://doi.org:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.06.007

24 Jagadish, A., Mills, M. & Mascia, M. B. Catalyzing conservation at scale: A practitioner’s handbook (version 0.1). (Conservation International and Imperial College London, Arlington USA and London, UK, 2021).

25 Strang, D. Adding social structure to diffusion models: An event history framework. Sociological Methods & Research19, 324-353 (1991). https://doi.org:10.1177/0049124191019003003

26 Glew, L., Mascia, M. B. & Pakiding, F. Solving the mystery of MPA performance: Monitoring social impacts. Field Manual (version 1.0). 1-358 (World Wildlife Fund and Universitas Negeri Papua, Washington D.C. and Manokwari, Indonesia., 2012).